The Complex Greek Meander

BY CALDER LOTH

Senior Architectural Historian for the Virginia Department of Historic Resources and Member of the Institute of Classical Architecture & Art Council of Advisors.

The terms Greek key, fret, and meander are all names for a decorative device employed on buildings and objects beginning in ancient Greece and continuing to modern times.[i] The device comes in a variety of forms. At its most basic, it is a band consisting of short horizontal and vertical fillets connected to each other at right angles. It has been called a Greek key because an individual section vaguely resembles a primitive key. The labeling of it as a meander results from its continuous back and forth progression, recalling the winding course of the Meander River in Asia Minor, now present-day Turkey. The unbroken, interlocking pattern made it a symbol of both unity and infinity. What I define as the complex Greek Meander consists of two parallel strips of meandering fillets crossing one another at continuous intervals. The designation is my own since I can find no specific definition for this distinctive form of Greek fret. This illustrated essay is intended to show the early origins of the complex Greek meander and to offer examples of its use as an embellishment for more than two millennia. I hope it might encourage the application of this timeless, visually engaging detail as an ornamental accent for contemporary classical architecture.

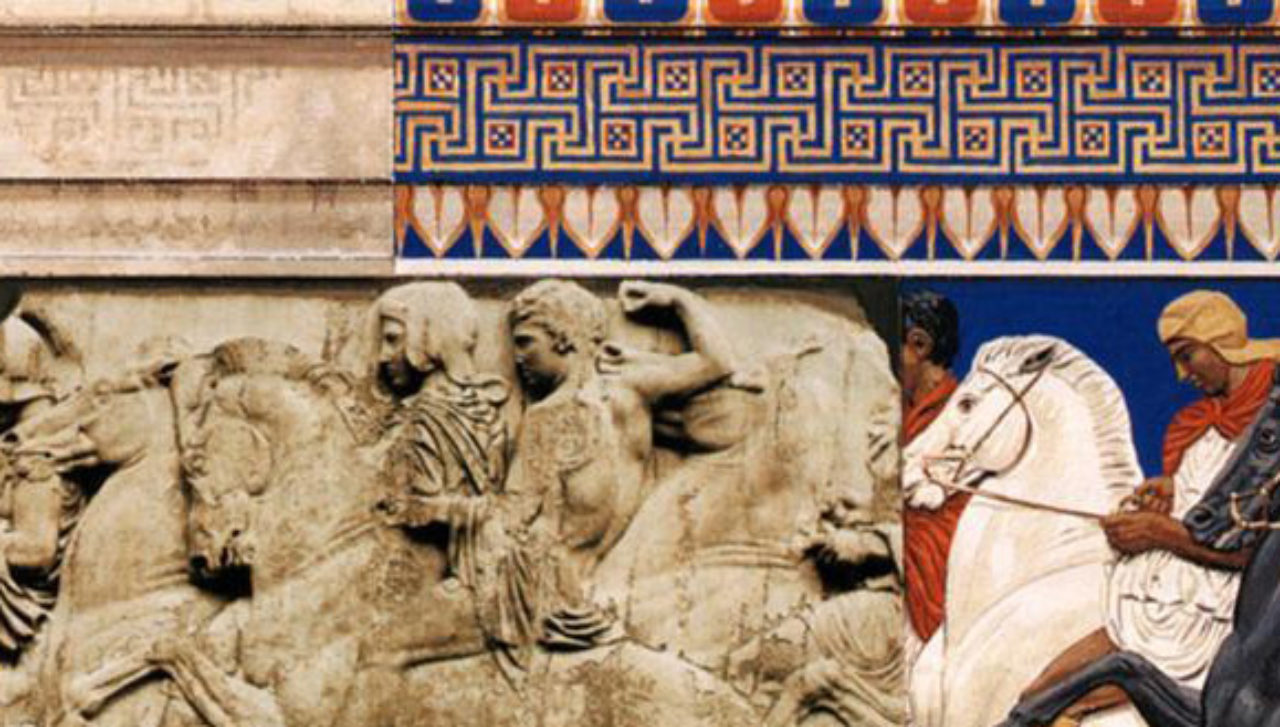

One of the oldest examples of the complex Greek meander as architectural ornamentation survives as faded painted decoration on the fascia above the Parthenon’s famous sculptural frieze depicting the Panathenaic festival.[ii] The motif has been expanded vertically and horizontally with the insertion of decorated squares at regular intervals. Scientific examination has shown that the band was originally richly colored as were all the sculptured figures in the frieze and those located elsewhere on the temple. The illustration of a short section, shown here, offers a conjectural reconstruction of the original color scheme for both the sculptures and the painted band and is contrasted with the present condition.

A very early depiction of the complex Greek meander is found not in a work of architecture but in a recently discovered object. In 1977, archaeologists working in northern Greece unearthed what is believed to be the tomb of Philip II of Macedon, father of Alexander the Great (died 354 B.C).[iii] Among the numerous artifacts found in the tomb was an elaborate ceremonial shield, richly decorated with figures and motifs in gold and ivory. A close look at the border shows a complex Greek meander worked into the pattern with ivory inlay. While the shield is an exceptional artifact, we should note that the meander was commonly used as a decorative band on Greek pottery, although the complex version is found infrequently on these ceramics.

The complex Greek meander received elevated status through incorporation in the band separating the upper figural panels from the lower panels of stylized acanthus ornaments on Rome’s Altar of Augustan Peace. Known more commonly as the Ara Pacis, the altar was consecrated in 9 B.C. to celebrate the abundance and peace brought to the Roman world by the emperor Augustus. Executed in pure white luna marble, the altar reveals the artistry of Roman sculpture at its most exquisite. It was wrecked and ultimately vanished from sight following the barbarian invasions of Rome. Fragments were discovered in 1568 and many of the panels were unearthed in late 19th Century archaeological investigations. The pieces were assembled into an anastylosis recreation of the altar in 1938, marking the 2000th anniversary of the birth Augustus. The Ara Pacis is currently housed in a protective pavilion designed by Richard Meier, completed in 2006 adjacent to the Mausoleum of Augustus in Rome. Shown is a detail of the east wall panel displaying members of the imperial household with a complex Greek meander band beneath.

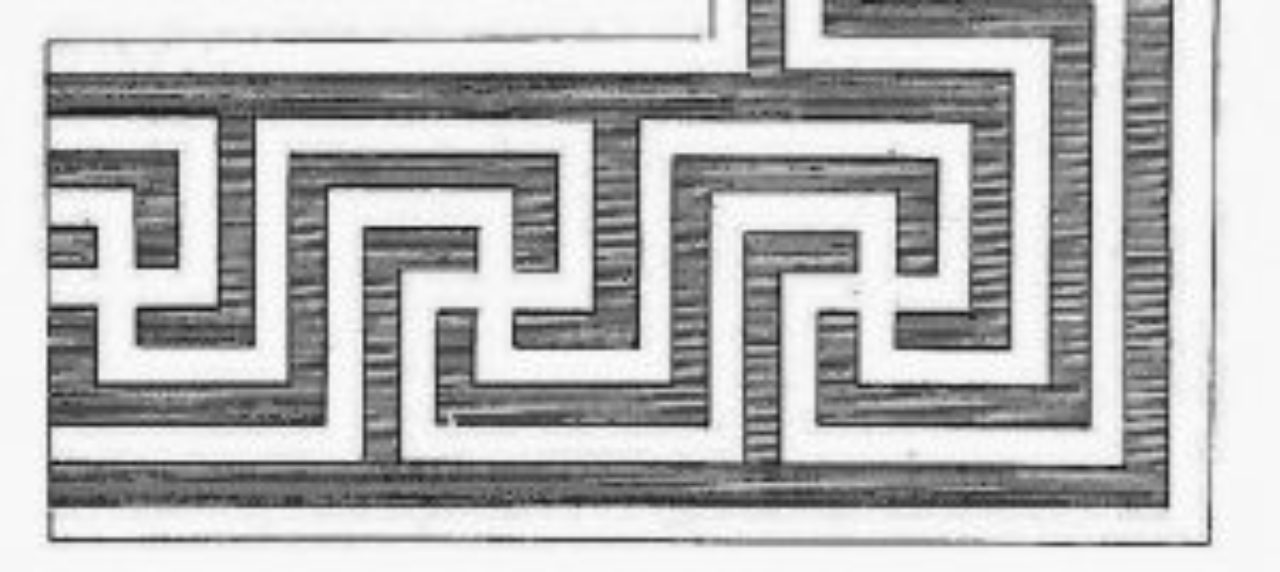

The Temple of Mars Ultor (Mars the Avenger) was the centerpiece of Rome’s Forum of Augustus, one of the main projects carried out by Emperor Augustus. Built of luna marble and completed in 2 B.C., the temple was where the Roman Senate met to discuss waging war, and where the trophies of victory were brought as tributes to Mars. The temple was plundered for its materials beginning in the 5th century. The principal surviving elements are three columns of the south elevation. They support an intact section of architrave, the soffit of which is decorated with panels enriched with bands of the complex Greek meander. Because of its location in the heart of Rome, this example of the motif was the principal one known to the Renaissance architects.

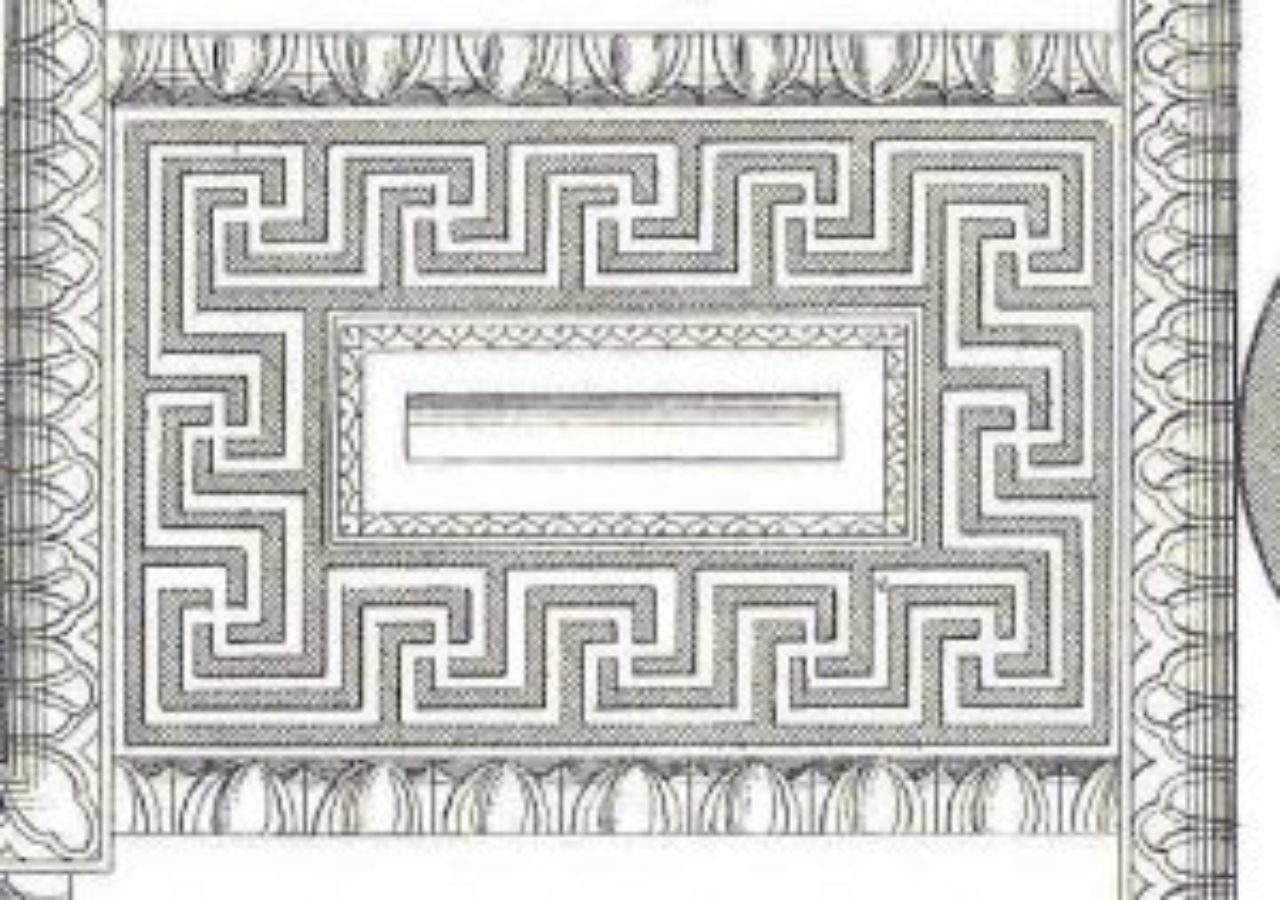

We may credit Andrea Palladio for making the complex Greek meander known to future generations. His indefatigable recording of Roman ruins and the subsequent publication of his findings, along with conjectural restorations in Book IV of Quattro Libri, provided design resources for architects henceforth. His illustrations included not only elevations, plans, and sections of ancient works, but many details. This material, which includes conjectural restorations as well as descriptive text, stands as a pioneering example of above-ground archaeological recordation and interpretation. Among his seven plates of woodcuts devoted to the Temple of Mars Ultor is a section of the portico soffit showing its panels enriched with the complex Greek meander. While this may not be the first published image of this detail, Palladio’s famous treatise certainly was the vehicle for introducing it to the broadest audience. Palladio doesn’t mention the meander specifically, but his text on the temple states: These porticoes have beautiful soffits, or, as I prefer to say, coffering, and I have drawn them in profile and projected them in plan.” [iv]

The use of the complex Greek meander spread throughout the Roman world, particularly during the empire period. One of the empire’s more distant cities, Baalbek, in present-day Lebanon, saw the construction of some of the most impressive edifices in Rome’s domain. Among them was the colossal Temple of Jupiter, the scale of which exceeded that of anything built in the city of Rome. Completed ca. 60 A.D. on the site of an earlier temple, it was largely pilfered for its materials around 397. In the 530s, the Emperor Justinian disassembled eight of the peristyle columns for reuse in Constantinople’s Hagia Sophia. Today, six of the enormous Corinthian columns, together with their entablature, remain in situ. At the base of its podium is a fallen section of the cornice with its fascia decorated with the complex Greek meander as well as one of the temple’s famous lion’s head gargoyles.

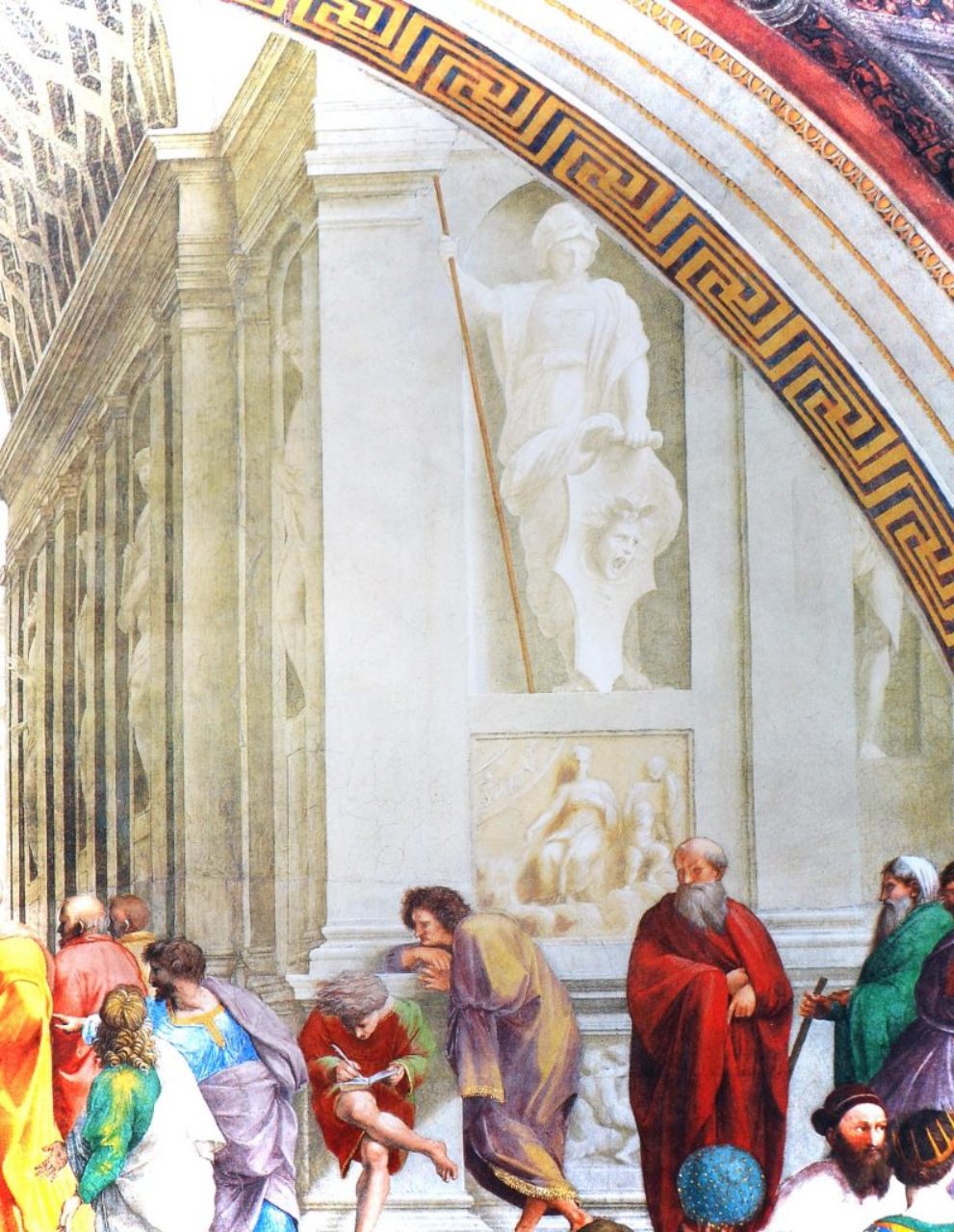

Awareness of the complex Greek meander enables us to note its presence in unsuspected places. Hence, in viewing Raphael’s famous Vatican fresco, School of Athens, we can spot the meander decorating the soffit of the arch framing the composition. This was one of the set of Stanze della Signatura murals executed by Raphael in 1509-11, decades before the meander was published by Palladio. Thus we ask, what was Raphael’s source for the motif? He may have seen it in some obscure early architectural treatise. We should remember that Raphael was an accomplished architect as well as a painter, however. His skill as an architect led him to serve as one of the architects for the rebuilding of St. Peter’s Basilica.[v] In 1515 he was named “Prefect” of all antiquities in Rome and vicinity. Thus we can appreciate that Raphael was well informed in classical design and classical details, and can assume that he early learned that the complex Greek meander was an effective and appropriate decorative device. Moreover, as a resident of Rome, Raphael was no doubt familiar with the ruins of the Temple of Mars Ultor.

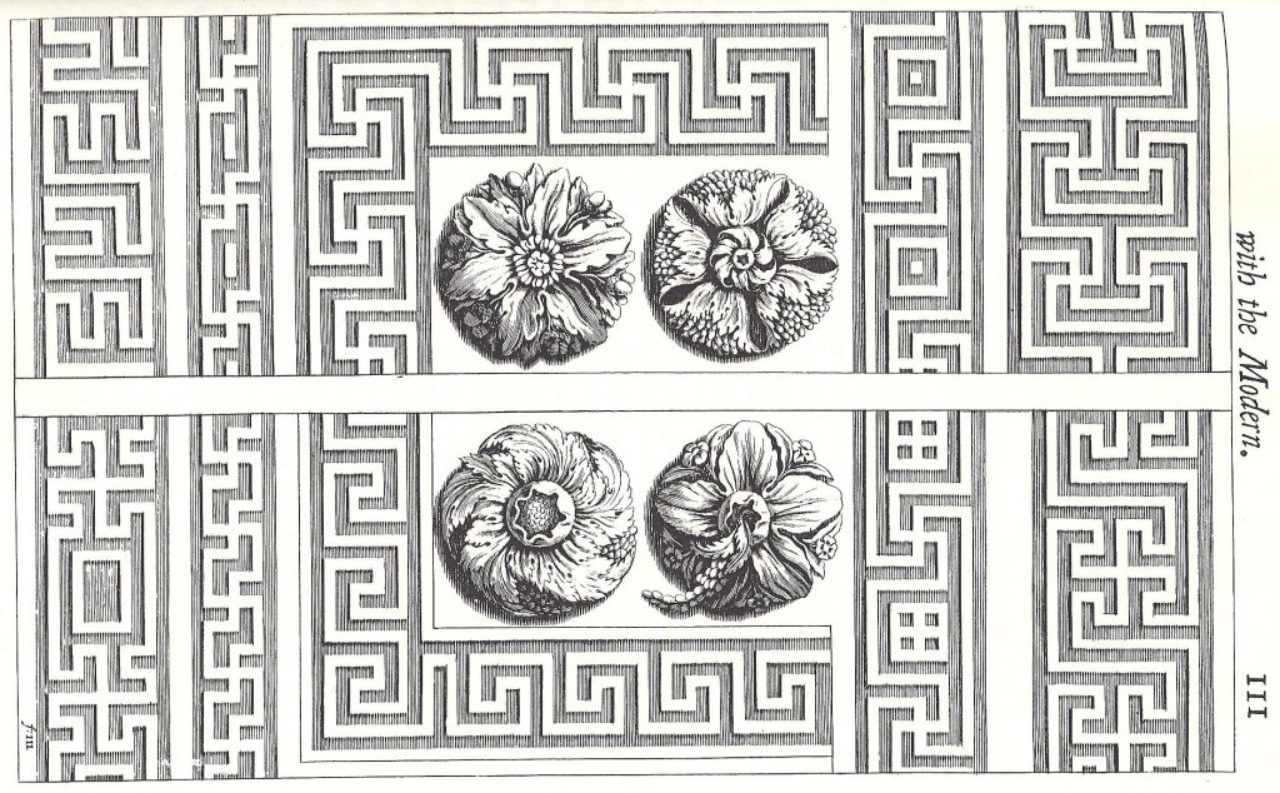

The French scholar, Roland Fréart, sieur de Chambray, undoubtedly became acquainted with the complex Greek meander during his 1630s sojourn in Rome, during which he studied architecture. Direct familiarity, however, was achieved when he translated Palladio’s Quattro Libri into French, published in 1650. That same year, Fréart published his famous Parallèle de l’Architecture antique et de la moderne in which he illustrated the page of frets shown here. The fret from the Temple of Mars Ultor soffit is seen in the center left. John Evelyn published an English translation of the Parallèle in 1664 from which Fréart’s commentary on the frets is here quoted: I have made a very curious and rare Collection of a certain Ornament which they call Fret, and of which the Antients [sic] made great use. . . . The Ornament consists in a certain interlacing of two Lists or small Fillets, which run always in parallel distances equal to their breadth, with this necessary condition, that at every return and intersection they do always fall into right angles; this is so indispensable that they have no grace without it.[vi]

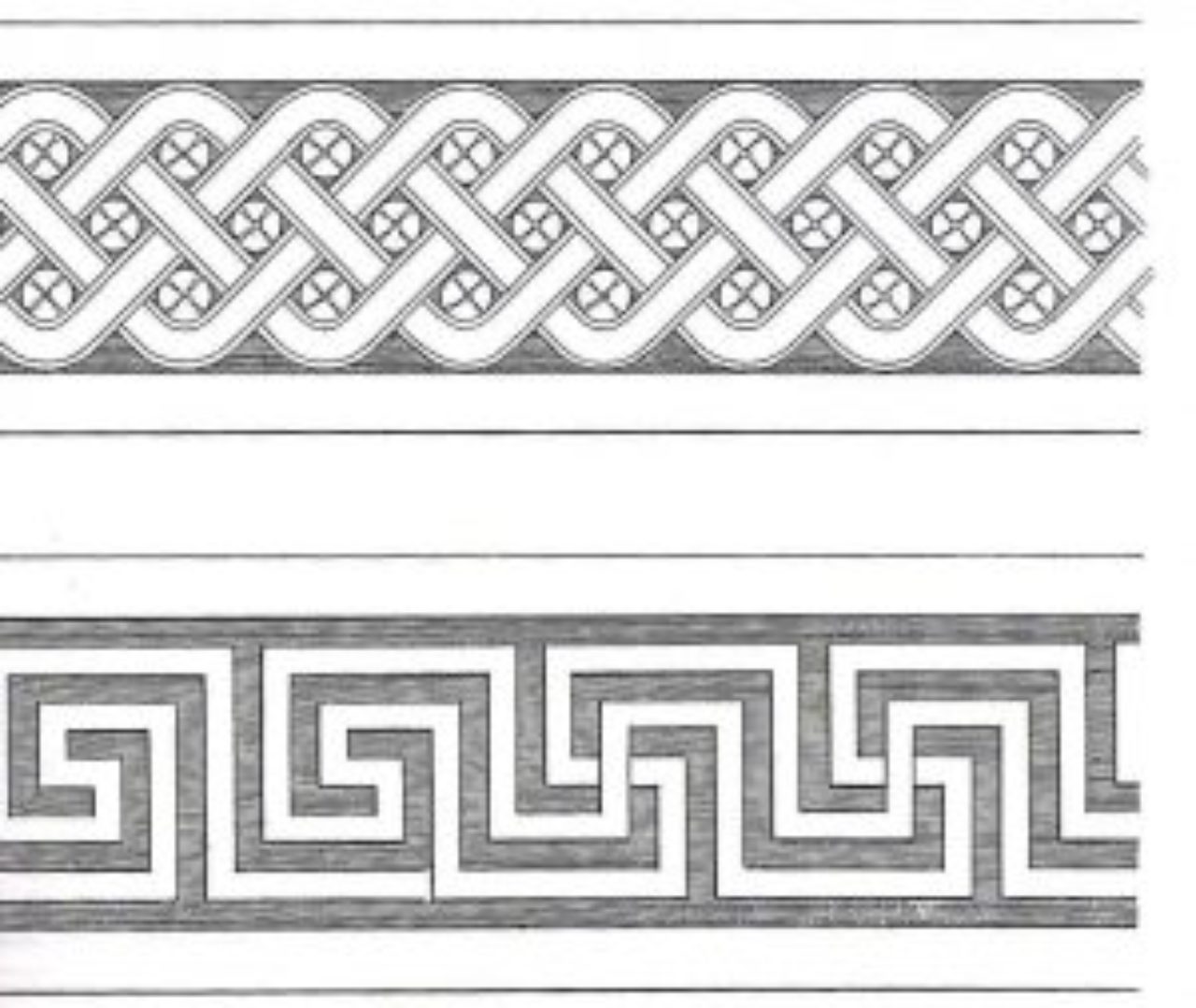

James Gibbs (1682-1754) was a leading architect in Britain’s Anglo-Palladian movement and is remembered for such works as the Fellows’ Building at King’s College, Cambridge and the Radcliffe Library at Oxford. His fame rests not only with his buildings, but with his two highly influential publications: A Book of Architecture (1728) and Rules for Drawing the Several Parts of Architecture (1732). The latter work, with his simplified method for drawing the orders and its numerous illustrations of architectural details, became a standard textbook for British Architects well into the 20th century. It also was an important reference for builders in colonial America. Among the many details Gibbs illustrated was the complex Greek meander, which he likely derived from either Palladio’s or Fréart’s publications. Gibbs described the meander as . . . a Fret-border of eleven different divisions done in two ways, the distances of the sinking and the rising being equal.[vii]

The complex Greek meander found its way onto the hall chimneypiece of Drayton Hall, the famous South Carolina Anglo-Palladian plantation house built for John Drayton in the 1750s. The overall design of the chimneypiece follows one published in The Designs of Inigo Jones (London, 1727) by William Kent.[viii] While the overmantel is a close copy of the published image, the mantel itself is a more straightforward scheme. Instead of swags in the mantel frieze, as shown by Kent, we find the complex Greek meander. Interestingly, an inventory of the Drayton Hall library, prepared by John Drayton’s son, Charles Drayton (died 1820), lists both Andrea Palladio’s The Four Books (Isaac Ware edition, 1738) and the John Evelyn 1664 English edition of Fréart’s Parallèle.[ix] As noted above, both books illustrate the complex Greek meander. We may safely speculate that these books were originally owned by John Drayton and were referred to in crafting many of Drayton Hall’s architectural details.

Illustrations of the complex Greek meander in such widely circulated treatises as those by Palladio, Fréart, and Gibbs, led to the inclusion of the detail in many 18th Century British architectural pattern books and builders’ manuals. These spread awareness of the motif ever wider, particularly in the English-speaking world. A partial list of publications having plates showing the meander include Edward Hoppus’ The Gentlemen’s and Builder’s Repository (1737), William Salmon’s Palladio Londinensis (second edition, 1738), Batty Langley’s The City and Country Builder’s and Workman’s Treasury of Designs (1740), Langley’s The Builder’s Director or Bench-Mate (1751), Abraham Swan’s The British Architect (1758), and William Pain’s The Builder’s Companion (1758). All of these books were available in the American colonies, hence without specific documentation it can be difficult to determine which might have been the source for the details in such prominent colonial mansions as Shirley in Virginia. The complex Greek meander decorates the frieze in the first-floor bedroom.

James Stuart and Nicholas Revett introduced us to the subtle beauties of ancient Greek architecture with their profusely illustrated three volumes of The Antiquities of Athens (published respectively in 1762, 1789 & 1795). Among the ruins they covered was the Tower of the Winds, a small octagonal structure in Athens’ Roman Agora. The tower served as the inspiration for the 1785 Temple of the Winds, a jewel-like banqueting house designed by Stuart for Mount Stewart, the Northern Ireland estate of John Stewart, future Marquess of Londonderry. The mantel in the temple’s main room is richly decorated with neoclassical ornaments, including a complex Greek meander band below the frieze. The mantel is attributed to the London carver and frame maker William Adair, who, with his brother John (died 1771), provided architectural details for both Stuart and Robert Adam. The complex Greek meander is not illustrated in either The Antiquities of Athens or Adam’s Works in Architecture. Nevertheless, the meander was a standard motif in the 18th-century architectural repertoire.

A familiarity with various classical motifs makes strolling city streets an unavoidable scavenger hunt. Most cities of any age hold buildings and structures expressed in the classical language. New York’s Fifth Avenue is no exception, although its famed collection of Gilded Age mansions has long been supplanted with commercial structures. A prominent example of the latter is the 1914 flagship store of Lord &Taylor, designed by Starrett & van Vleck, a firm known for its department stores. Attached to the landmark structure, at the corner of W 39th Street, is an anonymous earlier Beaux-Arts commercial building, now part of the Lord & Taylor establishment. The unidentified architect of this work decided to entertain the millions of passersby with an entablature at its main level displaying a properly fashioned complex Greek meander.[x] Regrettably, the fine detail is noticed by almost nobody, so we can only hope this ICAA blog will help bring it to peoples’ attention and make ambling Fifth Avenue a more enriching experience.

While I had hoped to offer a 21st Century example of the complex Greek meander, I have yet to find one, although one might indeed exist. Nevertheless, as a design of pure, straightforward geometry, its use would be compatible with architectural works of almost any style, particularly contemporary classicism.

______________________________________________________________

[i] Versions of the Greek key are also found on Chinese and Indian structures and objects, but they are another subject.

[ii] Most of the frieze was removed by Lord Elgin in the early 19th century and is now displayed in the British Museum, London. Sections of the faded fascia decorations remain in situ.

[iii] Some scholars have claimed that the tomb is not that of Philip II but rather Philip III, Alexander the Great’s half-brother, but forensic evidence derived from the human remains there make a better case that the tomb is that of Philip II.

[iv] Andrea Palladio, The Four Books on Architecture (1570), Book IV, Chapter VII, p 225. Translated by Robert Tavenor and Richard Schofield (MIT Press, 1997).

[v] What work Raphael was able to achieve for St. Peter’s was later removed for Michelangelo’s revised design.

[vi] Roland Fréart, Sieur de Chambray (John Evelyn translation), A Parallel of the Antient Architecture with the Modern (London, 1664), p. 108.

[vii] James Gibbs, Rules for Drawing the Several Parts of Architecture (London, 1732), p. 38.

[viii] Despite the title of this pattern book, the chimneypiece design was not by Inigo Jones, but rather by William Kent for a chimneypiece in Houghton Hall, Norfolk, England. The house was designed by Kent for Robert Walpole.

[ix] Patricia Ann Lowe, Volumes that Speak: The Architectural Books of the Drayton Hall Library Catalog and the Design of Drayton Hall. Graduate Thesis Project for the Graduate Schools of Clemson University and the College of Charleston (Charleston, S.C., 2010).

[x] The entablature’s cornice has unfortunately lost its crown molding.